Insidious side letters

SHADY BUSINESS

ON THE SIDE

By Thomas D. Gober, CFE, and Leslie N. Bailey, CFE

Undisclosed agreements – side letters – between an insurance company

and a reinsurer can hide egregious and fraudulent transactions from

regulators, investors, and consumers. Here’s how to find them.

An insurance company executive faces tremen- dous pressure as Dec. 31 approaches especially because the company’s balance sheet has deteri- orated below the financial ratio red-flag alerts. Worsening the situation is the fact that the executive has already cooked the books so much that the asset page has no room left for “fluffing up.” The home office building has already been reappraised by a cousin who helped surplus it by $900,000. And the executive continues to admit $3 million in notes receivable from an affiliated company at full value even though the affiliate hasn’t been able to pay the interest, much less principal, for three years. If he inflates any more assets, the regulator is likely to smell a

rat and move to shut him down.

The controller brings the executive the company’s Risk Based Capital (RBC) ratio calculation results on Dec. 21, and with the RBC comes bad news. The RBC ratio is 189 percent but it must be at least 200 percent or the state insurance commissioner will be forced to take regulatory action to protect the company’s policyholders. The only way to get the RBC above 200 percent is to create surplus. A traditional loan won’t work because the payable back to the lender is a liability that offsets the cash infusion from the loan; assets go up, but liabilities go up as well. Consequently, surplus isn’t increased.

The desperate executive e-mails a friend and col- league who is a vice president at a large

reinsurance com- pany and explains the situation. The executive needs an “off the balance sheet

loan” that provides a cash infu- sion, or at least the appearance of one, without having to book

the associated liability. But the infusion must appear to have no strings attached so the regulator

won’t become suspicious. The executive promises the perfect solution: the two key executives can enter into what appears to be a “plain vanilla” reinsurance contract that, on its face, transfers

millions of dollars of risk from the insurance company to the reinsurer. In secret, the parties

agree to enter into a side letter that actually spells out the true terms of the reinsurance

contract. The undis- closed side letter reveals the true nature of the contract– it’s actually an “off the balance sheet loan.” For obvi- ous reasons the two parties swear the side letter to secrecy.

At midnight on Dec. 31, the reinsurance contract combined with the undisclosed side letter has done the trick. RBC comes in at 203 percent, and bonuses are handed out. Several weeks later the

executive, out of fear and guilt, pulls up the incriminating e-mails exchanged with his colleague

and carefully deletes them. What he didn’t know was that his hard-working IT director backed up the entire computer system on Dec. 31 and stored the back-up tape safely offsite.

In the regulatory world, a “side letter” is perhaps the most insidious and destructive weapon in

the white-collar criminal’s arsenal. With the flick of a pen, underhanded executives can cook the

books in enormous amounts and render helpless a regulator (state insurance commissioners or the

Securities and Exchange Commission if publicly traded).

In the world of insurance and reinsurance, the term side letter is rarely muttered, much less

defined. Although the media has, more recently, focused on side letters encountered in the

insurance industry, they have been used in a wide variety of industries. For the purpos-

es of this article, consider it to be an undisclosed agreement between two parties (insurers and/or reinsurers) that has a direct and material affect on an existing disclosed reinsurance con- tract. Reinsurance is an agreement in which an insurance company transfers part or all of its risk of loss under insurance policies it writes through a separate contract or treaty with another insurance company. The insurance company providing the reinsurance protection is the Reinsuring Company or Reinsurer. The insurance company receiving the reinsurance protection is the Ceding Company.

The primary disclosed contract, in and of itself, is tradition- al in structure and terms, and it passes the “smell test.” The con- tract is acceptable because regulators, auditors, and others assume that the entire contract is contained “in the four cor- ners” of the document. What remains unseen are the undisclosed terms of the “side letter,” which materially change, or even render meaningless, the original contract terms.

I’ve been lucky enough to stumble on to a half dozen or so of these side letters in my career as a

forensic accountant, all of them in the world of insurance/reinsurance. Each of these side letters were negotiated between an insurer and its reinsurer to enable them to do, in secret, what they wouldn’t have been permitted to do otherwise. Side letters found by the fraud examiner are veri- table smoking guns. However, they’re rarely detected because the conspirators must keep side letters top secret lest the regulator piece together the true nature of the transaction. By then it’s usually too late.

them in the world of insurance/reinsurance. Each of these side letters were negotiated between an insurer and its reinsurer to enable them to do, in secret, what they wouldn’t have been permitted to do otherwise. Side letters found by the fraud examiner are veri- table smoking guns. However, they’re rarely detected because the conspirators must keep side letters top secret lest the regulator piece together the true nature of the transaction. By then it’s usually too late.

There are occasions when open and disclosed side letters are beneficial and justified from a business perspective. But in today’s environment of heightened scrutiny and paranoia resulting from such massive frauds as those alleged at Enron, WorldCom, and more recently AIG, fraud examiners and forensic accountants should err on the side of conservatism (full disclosure) and assume that most side letters are intended to deceive. If the sole goal of a side let- ter is to further explain that which is already addressed in a con- tract for which the side letter is penned, there’s little harm. However, the original contract should speak adequately for itself.

The March 31, 2005 release of MarketWatch, a financial news Web site and division of Dow Jones & Co., led with Alistair Barr’s headline that read “Side letters are no longer a side issue: AIG probe exposes secret deals that skew reinsurance.” The thrust of the report given by Barr emphasizes the severity of the problem the insurance industry is experiencing a series of egregious transactions conducted with deliberate intent to hide their dishonor from regulators, investors, and consumers.

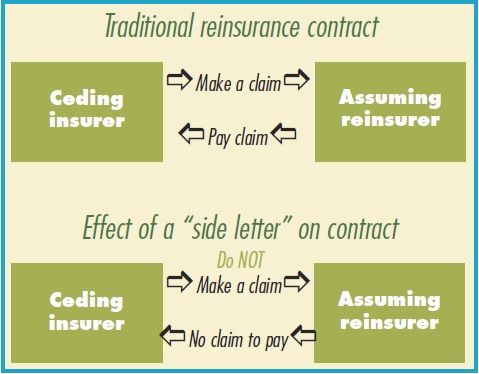

SIMPLIFIED EXAMPLE OF HOW A SIDE LETTER CAN AFFECT A CONTRACT

In the simple example shown in the illustration below, the terms of the traditional contract

require that if an event triggers a claim to be made by the insurer to the reinsurer, the

reinsurer must indemnify the insurer for that claim. The requirement for indemnification reduces

pressure on the ceding insurer’s surplus. By careful review of the financial statements, the ceding

insurer recognizes that the financial wherewithal of the ceding compa- ny is supported by the

assuming reinsurer’s financial strength.

If the two parties enter into a secret side letter that states that the ceding insurer will not

actually make claims as intended in the original contract, the reader of the ceding insurer’s financial statements are deceived. Bolstered by the false impression of surplus, the ceding company can write new policies lulling current policyholders to continue to remit their premiums.

For example, an insurance company intends to falsely inflate its surplus to prevent being taken over by the regulator. Assume that the insurer’s true sur- plus level is a negative

$100 million and the minimum required is a positive $10 million. Borrowing $120 mil- lion via a traditional loan won’t cure the problem because when the company debits cash for $120 million it must simultaneously credit a liability for the loan payable. Surplus isn’t improved. Besides, who wants to loan that kind of money to an insolvent insurer?

An ethical company would seek legitimate reinsurance by laying off (ceding) $120 million of real

insurance liabilities to a reinsurer. That reinsurer might consider taking on (assuming) the risk

if it anticipates that it will enjoy sufficient future premi- ums to be paid on that block of

business to cover its future liabilities. Under a legitimate scenario like this, the insurer can

increase its surplus commensurate with the shedding of its lia- bilities to the reinsurer. But

suppose there’s a problem, as is often

the case, with that block of business. Such a volatile block of high-risk business from

the ceding insurer may pose a higher risk than the reinsurer is willing to assume.

But the desperate insurer needs immediate relief and, in a panic, decides to step

over the fraud line.

Enter the secret side letter. If the two parties (insurer and reinsurer) agree to

enter into the aforementioned legitimate agreement to truly transfer the $120 million

in risk but secretly agree not to transfer the risk, the true nature of the

entire transaction is, in effect, a “loan” for which the borrower books no liability.

The troubled insurer creates an appearance of solvency, at least temporarily,

and the assuming reinsurer will be paid “premiums,” which are more accurately

described as loan “fees” and/or “interest.”

There are two serious problems with this type of arrangement. First, no one can

see the true nature of the transaction except the two parties who execute the

side letter. Second, the troubled insurer must pay significant consideration to the

reinsurer for which the insurer receives absolutely nothing of real value in return.

They basically pay rent for the right to make a book entry to falsely inflate their

surplus. The regulators, auditors, actuaries, rating services like A.M. Best, policyholders

and the public rely on the false strength of the insurer.

This example is somewhat oversimplified but not by much. Usually, the troubled

insurer starts out renting relatively small amounts of artificial surplus. But the

quick fix is like heroin to someone predisposed to addiction. The fast but momentary

high feels good, but the next time they want more. Soon, the need for false

inflation of surplus grows at a geometric rate and the cost rises, but the true value

of what’s actually purchased remains at zero.

DOMESTIC DISARRAY

The United States has become increasingly

aware of side letter schemes. Most of

them never surface. The insurers often

flipping is involved, it receives the focus. The side letter is too hard to find and much harder to understand. Witnesses to a side letter execution are few and far between.

Several recent domestic insurance company collapses have included allegations of side letter schemes. Investigations of those collapses have not yet been completed. Insurance industry experts

claim that there have been many more side letters in the world of insurance/reinsurance than people suspect. But other experts have said the day of the side letter has come to an end. Regardless, fraud examiners and forensic accountants hopefully will take heed and watch for the signs and symptoms.

Regulators and auditors should scrutinize all insurance companies that meet certain criteria indicative of dangerously thin surplus. Their reinsurance portfolios should be scoured for agreements that don’t pass the smell test. If premiums paid are not commensurate with the purported risk transfer or, more telling, if the actual cash flows between the two parties doesn’t track with the stated terms of the agreement, witnesses should be interviewed and all related correspondence should be scrutinized.

INTERNATIONAL SCOPE

The United States isn’t the only country to suffer from secretive side letter schemes. Fraudsters have actually targeted other some countries for questionable reinsurance deals because of their

obvious lack of regulatory oversight. It’s not a coincidence that countries associated with “offshore” transactions, like Bermuda, and cities like Dublin, Ireland, have seen tremendous growth in reinsurance transactions.

Recently a special commission formed by Australia’s government to investigate the largest insurance company collapse in the country’s history released a lengthy and detailed report of

its findings. After two years of combing through the documents and interviewing and deposing witnesses, Justice Neville Owen said that he found that many immoral and inappropriate business transactions were uncovered, but he summarized the findings by saying that perhaps

the worst criminal deeds at the heart of the collapse were the reinsurance transactions involving side letters. These documents reduced the reinsurance to nothing more than loans for which the corresponding liabilities weren’t booked.

THE WORST KIND OF LIE

As the complete dependency on false surplus inflation grows, so does the cost. The cost isn’t merely financial. Top management must devote more and more time to juggling the complex reinsurance schemes and less time to actually operating their insurance companies. Furthermore, crucial ratios upon which an insurer’s financial performance and liquidity are measured appear to be acceptable because of the false surplus booked in connection with the side letter scheme. Even needed remium rate increases are less likely to be sought and/or approved due to the false appearance of premium rate and surplus adequacy.

Regulators must be able to rely upon the sworn statutory financial statements filed by insurance companies. If the regulator, the auditor, the actuary, the rating service and the public are brazenly shown a perfectly compliant reinsurance agreement, while the hidden side letter secretly strips the agreement of its risk transfer, there’s little the regulator can do but hope the fraud examiner or forensic accountant finds it while sifting through the rubble.

Thomas D. Gober, CFE, is president and owner of Thomas

Gober Forensic Accounting Services Inc. His e-mail address is:

tdgober@tgfas.com.

Leslie N. Bailey, CFE, works for Regions Financial Corporation.

Her e-mail address is: leslie.bailey@regions.com.